Recent trends in drug abuse in China1

Introduction

Heroin abuse became a major concern in China in the 19th century, when western colonialists forcibly imported opium into the country. Before the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, approximately 5% of the entire population of mainland of China (approximately 20 million people) were addicted to opium. Following a 1949 national anti-drug campaign, China became “a country free from drugs”[1,2]. However, China has been facing the recurrence of pandemic drug abuse, especially heroin abuse, again since the late 1980s[3,4]. Drug trafficking and production have been increasing in China. 3,4-Methylenedioxymetham-pheta-mine (MDMA; also known as ecstasy), which emerged recently and is popular among young people, is the most abused drug, followed by opiates[4−6]. The aim of this review is to give a perspective of the current situation of drug abuse, the problems associated with it, especially HIV, and the strategy to control it in China.

Drug abuse sweeps across the country

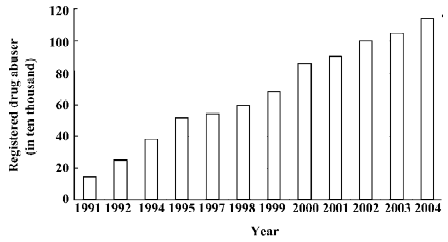

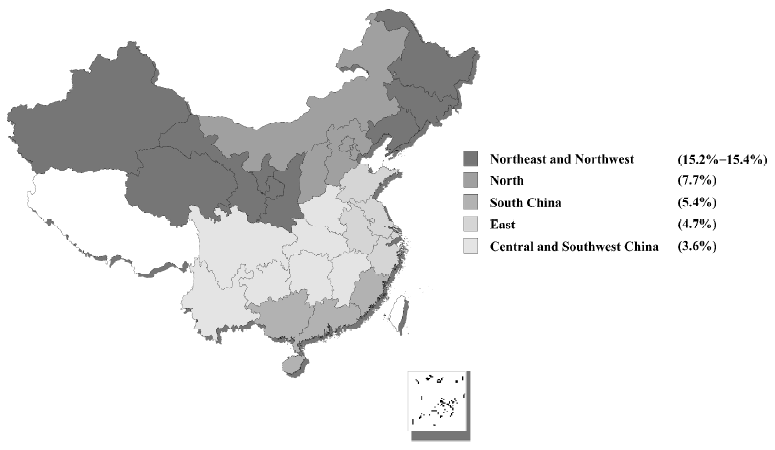

Beginning in the early 1990s, drug abuse spread quickly across China. The number of registered drug users increased from 70 000 in 1990 to more than one million by the end of 2004[7–9] (Figure 1). Most coastal cities in the country are affected, and the actual number of drug users is probably much higher than the official estimates. The drug abuse problem has spread to 2148 counties/cities, representing 72.7% of the total counties (or cities or districts) in China[7−9]. Furthermore, in recent times drug abuse has spread to undeveloped areas, especially in the northwest and central regions of the country (Figure 2). A 2003 survey shows that heroin is the most abused drug in China (89.34% of total abused drugs), followed by MDMA (5.37%) and other opiate substances such as morphine and methadone (2.25%)[3,8,9]. Most heroin abusers are male (M:F=1:0.22), young (55.7% are 26–35 years old, and 86.4% are 21−41 years old), unmarried (54.7%), and unemployed (64.5%), with a low educational level (81% have only a junior education or lower)[8,9]. For new drug abusers (who first used drugs in the past year), nasal inhalation is the main route of administration, whereas for experienced drug abusers, injection is the main method of delivery. According to surveys, most new drug abusers spend less than 2000 RMB (Chinese yuan) per month on drugs, whereas most experienced drug abusers spend more than 2000 RMB per month[8–10].

Illicit drug trafficking

In the early 1980s, international drug traffickers took advantage of the reforms and more open policies in China to smuggle drugs into the country, which resulted in drug abuse occurring in many southern cities. As the number of drug abusers increases, consumption and production also increase. Many drug producers have been captured in coastal cities since 2000, some of whom are immigrants from South Korea and Japan[5,6]. The main sources of opium smuggled into China were Afghanistan, Myanmar and Laos, and cannabis and synthetic drugs, such as methampheta-mine, have tended to be imported from Cambodia and North Korea, respectively[5,10,11]. In 2004, 98 000 drug-related cases were brought before the authorities (an increase of 61.4% compared with 1999), and 10 800 kg of heroin, 12 000 kg of opium, 2700 kg of methamphetamine, 3 000 000 tablets of ecstasy, 186 000 kg of opium poppies and 408 000 kg of precursor or raw materials for manufacturing drugs were confiscated by security staff[5,12].

A spokesman from the National Anti-drug Committee noted in 2004 that drugs have entered China from various sources, and that internal trafficking activities have become increasingly widespread[10,13]. Many Chinese provinces lie along the so-called “China Channel” of drug smuggling, which leads from the Golden Triangle (an area near the borders of Myanmar, Thailand and Laos) to Chinese cities and abroad, and passes through the provinces of Yunnan, Gui-zhou, Shanxi, Gansu and Guangzhou[9,13]. The China Channel became a drug trafficking route at the end of the 1980s. International drug smugglers used China’s reputation as a drug-free country to institute this new trafficking route from the Golden Triangle, the largest opiate processing centre in the world, to areas in Yunnan province, then to Sichuan, Guizhou, Hong Kong and Macao. Wenshan in Yunnan Province lies directly next to the Golden Triangle, and there is no physical barrier between the 2 areas. Guangzhou city, adjacent to Hong Kong, was the first place in China to be opened to the world and is now one of the centers for trafficking drugs to other Chinese cities and abroad[14,15]. The cities of Anshun, Chongqing, Xi’an and Lanzhou had long histories of opium use and production before the foundation of the People’s Republic of China in 1949[2,3,5]. According to a police report, approximately 90 000 suspected drug dealers were caught in 2003 and approximately 9290 kg of heroin and 3190 kg of methamphetamine were seized[8,9,13].

Now, in order to prevent illicit drug trafficking, the Chinese Department of States has founded a commission to battle drug production and distribution in cooperation with the police, the intelligence service, the health sector and the government’s legislative branch.

MDMA as an emerging drug

As the number of drug addicts increases and the drug abuse problem spreads, consumption of traditional drugs grows alongside increasing use of new kinds of drugs. It has been reported that although opiates, especially heroin, remain the most commonly used drugs, MDMA and methamphetamine have recently become popular “recreational” drugs in large or medium-sized Chinese cities[8,9]. MDMA belongs to the class of amphetamine-type stimulants (ATS), and is a synthetic drug that can be manufactured in 2 ways: from benzyl methyl ketone, or from ephedrine extracted from the medicinal herb ephedra[16–18]. The increasing illicit manufacture of ATS, particularly methamphetamine, in East and South-East Asia is a major concern. It has been estimated that more than 70% of all seizures of amphetamine in the world took place in East and South-East Asia, mainly in South Korea, Japan, China and Thailand[5,19,20]. A dramatic increase in MDMA trafficking has occurred throughout the region, and illegal MDMA laboratories have been discovered in mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Malaysia, and most notably Indonesia[5]. The increased demand for ecstasy and the ready availability of precursor chemicals from China and Vietnam make South-East Asian nations increasingly vulnerable to becoming havens for large-scale MDMA manufacture[5,20]. In China, the countryside also faces a growing problem of ATS abuse[7,21]. In addition to its use in mainland China, ecstasy has become especially widely used in Macao and Hong Kong, the 2 Special Administrative Zones of China[13,14].

Drug use at “rave” parties has been growing in China, and the drugs most frequently encountered at raves are phenethylamine type stimulants (PTS) including ecstasy, methamphetamine, and ketamine[8,9]. According to the 2003 report of the Chinese Drug Surveillance Center, MDMA, methamphetamine and ketamine account for 5.6% of drugs used by new drug abusers, second only to opiates[8]. A comparison between experienced drug abusers and new drug abusers with respect to the most abused stimulants reveals that experienced drug abusers use more MDMA (0.13% for new drug abusers, versus 5.37% for experienced drug abusers) and methamphetamine (0.05% for new drug abusers, versus 0.19% for experienced drug abusers). MDMA is the most abused drug among young people. First-time MDMA users are getting younger, but the number of adults abusing ecstasy is also on the rise.

HIV among drug users

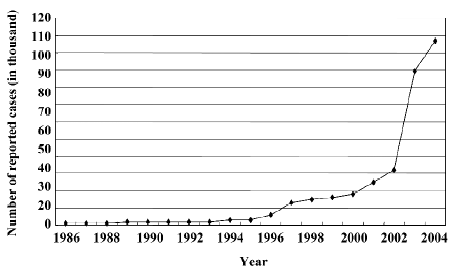

Drug abuse has led to many problems, in particular HIV/AIDS. In Asia and the Pacific, more than one million people acquired HIV in 2003, bringing the total to 7.2 million infected people in the region[6,13]. The growth of the epidemic in this area is largely due to the growing epidemic in China, in which a million people are living with HIV. China’s AIDS epidemic began in the early 1990s among injecting heroin users[22,23]. Injecting drug users account for more than half of China’s HIV infections. In addition, many of China’s sex workers inject drugs, and thus provide a bridge for HIV transmission to the general population[24–26]. As the commercial sex industry has exploded in China over the past 2 decades, HIV infection rates have also increased dramatically[22,26]. By the end of 2003, the number of registered HIV infections was 62 159 (including 2693 cases of AIDS, from which 1047 people died). An estimated 106 990 Chinese people were HIV positive by the end of 2004 (Figure 3). HIV infections have been reported in 31 provinces, autonomous regions, and municipa-lities, and the actual number of cases and spread of infection is likely much greater[22,23]. Drug abusers accounted for 63.7% of HIV cases. China is now one of the 6 South-East Asian countries in which there is growing ATS use, and vulnerability to HIV/AIDS appears to have increased[15,22].

It is well known that AIDS affects not only patients, but their families, society, and the economy. China’s first law targeting the disease was passed by the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress in 2004. Discriminating against the victims of infectious diseases has also been outlawed. Many efforts and measures have been adopted by the Central Government to help patients obtain effective treatment. As for preventing HIV spread among drug addicts, some places in China, such as Guangzhou province, are instituting needle exchange programs among drug abusers in order to break the HIV-heroin connection. Some areas are also advocating 100% condom use among sex workers.

Comments and recommendations

In recent years, China’s government has paid a great deal of attention to drug abuse, and has implemented strategies to control it, especially in terms of drug prevention and intervention. For instance, in 2002 the Chinese NNCC, together with 3 other Ministries, issued an important announcement about the strengthening of drug prevention work. Newspapers such as the People’s Daily, Fazhi Daily, and China’s Youth, set up special pages for drug education[11,12]. Organizations such as the culture, health, civil administration, youth, women and workers’ unions all joined in this work. Because most drug abusers are young people, the Ministry of Education now requires students from the fifth grade of primary school to the second grade of senior middle school to attend classes on drug prevention[6,12]. Intervention work has also begun in regions where the drug abuse and HIV/AIDS problems are serious. Drug abusers are given help in remaining drug free by their communities after being released from detoxification settings. Programs such as the China–UK HIV/STD Prevention Project are helping to carry out harm reduction programs among drug abusers and sex workers in Sichuan and Yunnan provinces[12]. More than 252 000 people were sent to drug rehabilitation programs last year, according to police statistics[8,9]. Chinese law stipulates that people found using drugs must be detained for up to 15 days, and that those found to be addicted to drugs be sent for rehabilita-tion. Strict law enforcement and intensive public awareness and prevention activities are indispensable in protecting young people from drug abuse.

Drug addiction is characterized by high rates of relapse and long-lasting vulnerability to drug-taking behaviors[27–29]. Relapse can be induced by environmental cues, stress and the drug itself [29–31]. The main challenge for addiction treatment is the prevention of relapse[32,33]. Many measures for the maintenance of drug-free states in addicts who abstain from drug abuse have been instituted in China; however, effective strategies are still lacking[3,6]. Strong measures are necessary, but alone these are insufficient to control drug abuse; changing public attitudes is also very important[34,35]. Drug abusers are often deserted by their families and friends. Even after ending their drug use, they are still rejected and looked down upon by the community: a situation which might lead to relapse. For drug abusers, psychological help is necessary, especially support from relatives, friends and colleagues. Therefore, the public must change its attitudes towards drug abusers, and accept them and help them instead of abandoning them[34,35]. In Hong Kong, some institutes for drug abstinence have set up a psychological treatment center to accelerate recovery; in addition, some workshops have also been set up to provide recovering addicts with employment[13,14]. In some areas, social workers offer recovering drug abusers job training. This kind of help is of great value to drug abusers.

In 2004, NNCC Director and Public Security Minister Yong-kang Zhou stated that the situation was very serious, and that there was much work to be done on narcotics control in China[7,10]. According to Minister Zhou, the government will intensify its struggle to stop drugs entering China, especially in Southwest China’s Yunnan Province and South China’s Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, and step up efforts to control chemicals used in the production of illegal drugs, such as ephedrine. Moreover, new technologies such as drug detectors will be given to police and intelligence networks to assist in the fight against drug importation.

As for the dramatic increase in HIV/AIDS infections among drug abusers, the government should implement a program of action that would follow international “best practice”[6,13,15]. First, the government should mount a multisector response and employ social science methods and approaches to the design and evaluation of anti-drug policies and pro-grams. Second, legislation is needed to support clean syringe exchange, methadone replacement and voluntary HIV tests among the public and to protect the rights and privacy of HIV-infected people. Third, a national HIV/AIDS and drug abuse public education program should be delivered to every Chinese citizen, especially those at highest risk. For example, among young people (high school students, unemployed young people, migrant workers, and teenagers and those aged in their 20s in less developed areas) the drug abuse situation is even worse. Fourth, HIV prevention efforts for drug users and sex workers will also require partnership with China’s Public Security Bureau and police at all levels, as will a major attitude change in the population. Finally, health services and workers should be deployed to mitigate the HIV epidemic, and the required drugs for HIV treatment should be added to formularies and essential drug lists and made available at reasonable prices.

In summary, drug abuse and HIV infection are increasing in China at an alarming rate, and require strong, effective, and immediate interventions.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Emily WENTZELL (National Institute on Drug Abuse, NIH, USA) and the NCI, CCR Editorial Board of the National Institutes of Health for editorial assistance.

References

- Lowinger P. How the People’s Republic of China solved the drug abuse problem. Am J Chin Med 1973;1:275-82.

- Lowinger P. The solution to narcotic addiction in the People’s Republic of China. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 1977;4:165-78.

- Zhao C, Liu Z, Zhao D, Liu Y, Liang J, Tang Y, et al. Drug abuse in China. Ann NY Acad Sci 2004;1025:439-45.

- National Institute on Drug Dependence and Drug Abuse Surveillance Center. Report of drug surveillance 2002. Beijing: NDASC, NIDD; 2002.

- Kulsudjarit K. Drug problem in southeast and southwest Asia. Ann NY Acad Sci 2004;1025:446-57.

- Kaufman J, Jing J. China and AIDS: the time to act is now. Science 2002;296:2339-40.

- National Anti-drug Committee. Anti-drug forum 2004; July 7–9, Beijing.

- National Institute on Drug Dependence and Drug Abuse Surveillance Center. Report of drug surveillance 2003. Beijing: NDASC, NIDD; 2003.

- National Institute on Drug Dependence and National Drug Abuse Surveillance Center. Report of drug surveillance 2004. Beijing: NDASC, NIDD; 2004.

- Li F. Education, prevention crucial to drug control. China Daily; 2004 June 26. Beijing, China.

- China UN Theme Group on HIV/AIDS for the UN Country Team in China. HIV/AIDS: China’s titanic peril (2001 Update of the AIDS situation and needs assessment report). Beijing: UNAIDS; 2001.

- Jing J, Zhang Y. HIV/AIDS and China’s ethnic groups. In: Workshop on Changing Health Needs and Reproductive Health Services; 2002 June 4, Beijing. Beijing: China Health Economics Institute, Ministry of Health.

- China-UK Workshop on HIV/AIDS in China. Annual report of China-UK HIV/AIDS Prevention and Care Project. Beijing: China-UK Workshop on HIV/AIDS in China; 2004.

- Lau JT, Kim JH, Tsui HY. Prevalence, health outcomes, and patterns of psychotropic substance use in a Chinese population in Hong Kong: a population-based study. Subst Use Misuse 2005;40:187-20.

- Aceijas C, Stimson GV, Hickman M, Rhodes T. Global overview of injecting drug use and HIV infection among injecting drug users. AIDS 2004;18:2295-303.

- Morton J. Ecstasy: pharmacology and neurotoxicity. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2005;5:79-86.

- Parrott AC. MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine) or ecstasy: the neuropsychobiological implications of taking it at dances and raves. Neuropsychobiology 2004;50:329-35.

- Hanson GR, Rau KS, Fleckenstein AE. The methamphetamine experience: a NIDA partnership. Neuropharmacology 2004;47 Suppl 1:92-100.

- Chung H, Park M, Hahn E, Choi H, Choi H, Lim M. Recent trends of drug abuse and drug-associated deaths in Korea. Ann NY Acad Sci 2004;1025:458-64.

- Beyrer C, Razak MH, Lisam K, Chen J, Lui W, Yu XF. Overland heroin trafficking routes and HIV-1 spread in south and south-east Asia. AIDS 2000;14:75-83.

- Hao W, Xiao S, Liu T, Young D, Chen S, Zhang D, et al. The second National Epidemiological Survey on illicit drug use at six high-prevalence areas in China: prevalence rates and use patterns. Addiction 2002;97:1305-15.

- Yang H, Li X, Stanton B, Liu H, Liu H, Wang N, Fang X, et al. Heterosexual transmission of HIV in China: a systematic review of behavioral studies in the past two decades. Sex Transm Dis 2005;32:270-80.

- Zeng Y. HIV infection and AIDS in China. Arch AIDS Res 1992;6:1-5.

- Ruan Y, Qin G, Liu S, Qian H, Zhang L, Zhou F, et al. HIV incidence and factors contributed to retention in a 12-month follow-up study of injection drug users in Sichuan Province, China. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2005;39:459-63.

- Kerr C. Sexual transmission propels China’s HIV epidemic. Lancet Infect Dis 2005;5:474.

- Lau JT, Feng T, Lin X, Wang Q, Tsui HY. Needle sharing and sex-related risk behaviours among drug users in Shenzhen, a city in Guangdong, southern China. AIDS Care 2005;17:166-81.

- Lu L, Chen H, Su W, Ge X, Yue W, Su F, et al. Role of withdrawal in reinstatement of morphine-conditioned place preference. Psychopharmacology 2005;181:90-100.

- Lu L, Dempsey J. Cocaine seeking over extended withdrawal periods in rats: time dependent increases of responding induced by heroin priming over the first 3 months. Psychopharmacology 2004;176:109-14.

- Shaham Y, Shalev U, Lu L, de Wit H, Stewart J. The reinstatement model of drug relapse: history, methodology and major findings. Psychopharmacology 2003;168:3-20.

- Lu L, Shepard JD, Scott Hall F, Shaham Y. Effect of environmental stressors on opiate and psychostimulant reinforcement, reinstatement and discrimination in rats: a review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2003;27:457-91.

- Wang X, Cen X, Lu L. Noradrenaline in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis is critical for stress-induced reactivation of morphine-conditioned place preference in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 2001;432:153-61.

- O’Brien CP. A range of research-based pharmacotherapies for addiction. Science 1997;278:66-70.

- Mendelson JH, Mello NK. Management of cocaine abuse and dependence. N Engl J Med 1996;334:965-72.

- Tang YL, Wiste A, Mao PX, Hou YZ. Attitudes, knowledge, and perceptions of Chinese doctors toward drug abuse. J Subst Abuse Treat 2005;29:215-20.

- Fok MS, Tsang WY. Development of an instrument measuring Chinese adolescent beliefs and attitudes towards substance abuse. J Clin Nurs 2005;14:986-94.